There’s a

certain song in Shakespeare’s ‘The Two Gentlemen of Verona’ that my father would

occasionally recite while my mother preened. It starts like this:

‘Who is Silvia?

What is she, that all our swains commend her?’

and this is

the question we’ll explore in these next few minutes.

The only place to start a eulogy for Sylvia Hilda Jane Harvey née Hill is half a mile from this church, at 12 Douglas Road, Horfield, Bristol, where she was born on 12th April 1928,

the eldest girl in a family of 13. She wasn’t Jack and Hilda Hill’s first

daughter: that was Barbara, their firstborn, who died at the age of five weeks.

There followed three boys –Mum’s elder brothers, Meric, Keith and Noel – and

then Jack finally got to delight in his blue-eyed girl. I think it’s fair to

say that Mum had him wrapped around her little finger for the rest of his life.

I recall my grandmother Hilda telling me of her indignation that decisions requiring

the attention of husband and wife always had to be run past Mum: ‘Let’s see

what Sylvia thinks first,’ Jack would say.

Being the

eldest girl in such a large family meant that a lot of the chores fell to Mum, particularly

from the age of 11, when Hilda

produced her hat-trick of babies. Mum specifically remembered being called into

the house to help when it was feeding time, with her taking a bottle and a

triplet, and whichever friends she was playing with arming themselves likewise.

She was a clever girl, but she failed the oral part of the entrance exam for

Red Maids School, leaving Hilda and Jack wondering whether the help she’d given

around the home had wrecked her education. They did the next best thing for

her, however, and cashed in an insurance policy so that Mum could attend a six-week

course in typing and shorthand, and she started to earn her living the day

after her 14th birthday. Mum had several employers, including a

stint at the BAC where she found typing columns of numbers extremely dull, but most

of her working life was spent as a legal secretary at J W Ward & Son in

Albion Chambers, where she acquired the nickname ‘The White Whirlwind’ from her

habit of doing everything at top speed. One day her boss, Malcolm Ward, gave

her a piece of paper and told her to type what was on it. Mum didn’t realise he

was standing behind her with a stopwatch, and when she’d finished, he told her

she was fractions of a second outside the world speed record for typing.

I need to

say a bit more about that childhood, though: a close-knit bunch of children;

concert parties in the back garden with Mum the star turn; illicit Woodbines on

the tump at the bottom of Douglas Road; long bike rides to Blaise Castle,

Clevedon and beyond, with a picnic of jam or paste sandwiches. It was, of

course, impossible for two such hard-pressed parents as Jack and Hilda to keep

a close eye on all those children, which meant that Mum and Uncle Noel, who was

closest in age to her, also got up to a fair bit of mischief. A few years back,

as their minds were beginning to drop their guard, I heard stories over lunch

at the former Royal George that would make your toes curl, but which are

probably best not shared today, in this hallowed place.

It feels

wrong somehow that Meric, Keith and Noel aren’t here today, for Mum idolised

them. I think her proudest possessions were the letters and the embossed leather

purse Meric sent her from Egypt, where he served in the Army during the

war.

In such a

large family there must have been a lot of rivalry for parental attention, and

this seems to have shaped the characters of many of the Hill siblings. I

remember the word ‘competitive’ featuring in Uncle Keith’s eulogy, and it’s

also one of the first adjectives I would choose to characterise Mum. She would

compete at anything she was good at, from tennis and badminton to housekeeping,

and she had a ferocious drive to win, as anyone who’s been on the receiving end

of one of her shuttlecocks can testify. In a family that prized boys above

girls, I think it was a disappointment to her that she didn’t have a strapping

son, and that her two daughters turned out to be decidedly un-athletic, but she

remained extremely proud of all of her rugby-playing brothers, not to mention

her grandson Dave’s rugby career during his teens, and latterly she would pore

over newspaper cuttings detailing the progress of my cousin Yvonne’s son Noah at

Worcester Warriors.

The family,

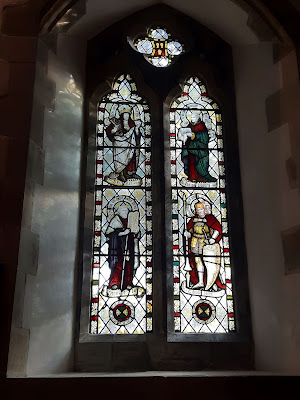

then, was the centre of Mum’s life. So, too, was her faith, which attached itself

firmly to the church we’re in today. Eden Grove also provided the raw material

for the more worldly part of her life, for it was here, in the Youth Club, that

she met Lionel Harvey, a football-playing ex-RAF serviceman, and it wasn’t long

before she’d converted him into a Bristol Rugby Club fan, with him selling his

car to buy Mum an engagement ring brilliant enough to match her megawatt smile.

She also made many lifelong friends here, among them Betty and Harold

Daveridge, Edith and Roy Ridsdale, Joy and Norman Hale – familiar presences in Linda’s

and my childhood, whose names were all prefixed with either Auntie or Uncle … as

if we didn’t have enough of those already.

It’s only

these last few months that she stopped her fundraising efforts for Eden Grove.

These mostly took the form of knitting, the clack of needles being the

soundtrack to her later, more sedentary years. Her handicraft stalls raised

thousands for this church, almost all in denominations of little more than a

pound. She was deeply saddened by the announcement of its forthcoming closure, a

decision which appeared to trigger a literal race to the death between Mum and the

Grove. We’re pleased Mum won it – of course she did! – and that we can say

goodbye to her here on All Saints Day.

Another

important place that featured in Mum’s service to the community was Filton Folk

Centre. She was a prominent member of the Community Association from its

earliest days, and her involvement was extensive. At one point, in addition to her full-time

job, she was running three early evening junior badminton clubs and the senior

badminton club on a Wednesday night, as well as organising the weekly Bingo

sessions on a Saturday evening. These were the association’s biggest

fund-raiser, and involved frequent trips to George’s Wholesalers on Victoria

Street for tombola prizes, the most prestigious of which featured a cardboard

box wrapped in a leftover piece of wallpaper and filled with tinned food, a

covering of cellophane and a sticky-backed rosette providing the finishing

touch. Mum was in her element as Queen Bee of the Folk Centre, and once again

she was conjuring valuable funds from very little other than her own hard work.

Mum was

joined at the Folk Centre on Saturday nights by her sister, Mavis, who did her

own valuable fund-raising in the form of the Sales Table. Auntie Mave, Uncle

Den and our cousins, Joy and Sandra, were also frequent companions on holiday

at Smugglers Caravan Park in Devon, and I can still see the sisters marching

along the sea wall to Teignmouth, or comparing bargain balls of wool bought at

Newton Abbot Market. What a loss Mavis was during those middle years. Crying

was considered a sign of weakness by Mum, and one of the very few times I saw

her eyes brim with tears was for her darker, quieter sister.

Throughout

her life Mum played to her strengths brilliantly. When Jennifer and Samuel were

diagnosed with autism, she offered unstinting practical assistance, cycling the

two miles from her house to mine and transporting one or other of the children

on her bike to wherever they needed to go. My children have very clear memories

of their Nanny scrubbing them to within an inch of their lives in the tiny

yellow bath kept under the caravan, and all of the grandchildren remember her reading

them bedtime stories, finishing with a fervent rendition of ‘You Are My Sunshine’,

a song we sang together again in her final days.

I suspect

that, in Mum’s eyes, illness and the depredations of old age were for other

people, not her, a notion perhaps reinforced by her recovery from breast cancer

at the age of 50. Certainly Mum and Dad were intent on remaining as independent

as possible for as long as possible, and for some years they propped each other

up, a bit like a pair of playing cards. Even after Dad’s sudden death in 2018 Mum stuck it out at 7 Kenmore Drive for another year and a half, and would have

continued to do so, I think, had she not broken her hip while picking

blackcurrants in the back garden. It was then she finally accepted it was her

turn to be cared for, and went to live in Nottingham. I’d like to thank all of the

Boston family for what they did for Mum during those final months, but

especially Linda, Alan and Ruth, who looked after her diligently, and were

unfailingly patient and kind as her physical and mental health diminished.

Mum was a

proud woman, and as hard as it was for us to witness her decline, it was

infinitely harder for her to endure it. She died on 29th September –

Michaelmas Day – and we’re relieved she’s no longer suffering.

I returned

to ‘The Two Gentlemen of Verona’ to find an ending for this eulogy, and came

across the love-lorn Valentine’s speech in Act 3 Scene 1, in which he contemplates

a life without Silvia:

‘What light is light, if Silvia be not seen?

What joy is joy, if Silvia be not by?

Unless it be to think that she is by

And feed upon the shadow of perfection.

Except I be by Silvia in the night,

There is no music in the nightingale;

Unless I look on Silvia in the day,

There is no day for me to look upon.

She is my essence, and I leave to be

If I be not by her fair influence

Fostered, illumined, cherished, kept alive.’

On first reading, this lament seems fitting. Mum’s

death is another of those huge shifts in our family’s shared story, and things can

never be the same without her. Yet she wouldn’t want us to grieve. I rather think

her parting challenge to us is to give our noses a good blow, stand up straight,

and get on with the hard work of living.